Cargo 200. Experimental projections on surfaces

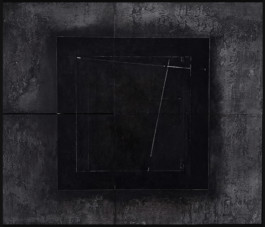

Installation view, Cargo 200. Experimental projections on surfaces. 5.7., 60 × 70 × 9 cm, variable dimensions (pine wood planks), Acrylic, gesso and wooden board, pine wood planks, Installation view at Kuenstlerhaus Sootbörn, Hamburg, DE, 2024

The long wooden elements in the installation Cargo 200. Experimental Projections on Surfaces. 5.7. are constructivist details, referencing the dream of a better world once envisioned by the constructivists. But what went wrong? We are now living in that imagined "future," and yet a better world remains out of reach. This work also employs the technique of iconography, though without specific religious figures. The black square represents a burial site. Since we do not know all the dead, their names, their stories, we can barely make out a few coffins in the overhead projection. The piece, taken as a whole, speaks to war as a broader phenomenon, not just a comment on current events. Through her visual and symbolic language, the artist addresses the cyclical recurrence of world-historical events. Themes of violence and resistance are deeply embedded in the human condition. Our capacity to adapt to the senselessness of war and tragedy, regardless of scale, stands in stark contrast to our awareness of their devastating consequences. Catastrophes leave indelible scars on the human soul.

Sofiia’s work does not offer comfort or resolution. Instead, it demands engagement—a challenge to viewers to recognize their role within the cycles of history and to reflect on the choices that either sustain or disrupt them. Violence does not return—it never leaves. Resistance is not heroism, but the final tremor of a being unwilling to yield to the void. The artist offers no salvation; she charts the anatomy of despair, showing that lucidity is not a virtue, but a burden too heavy for most to bear.

Cargo 200 is a term from military jargon. It refers to the transport of those killed in war back home. For the transport, the body of the deceased is placed in a special container, usually made of zinc. In my project, I use the method of “objectification” of my subjective war experiences by intuitively re-enacting the death of fellow citizens and soldiers through an experimental “an-ordering” on surfaces. This process captures the event rationally and insensitively, which is known to be a consequence of habituation to war. In war, the imaginary has no connection with reality. The traumatic nature of the reality of war is beyond our imagination. Overcome by this reality, we nevertheless cannot comprehend the fear of the possibility of our own death, which is unimaginable to us. When we think about our own death, we can be horrified, but when we talk about the death of thousands, the impossibility of mathematically multiplying the horror prevents us from trying to comprehend it. The world of war is made up of its own signs, most of which have hardly changed over the millennia. It is a series of archaic symbols that stand for center/periphery, order/chaos, vertical/horizontal, good/evil, life/death, victory/defeat, friend/foe. This series of works explores the problem of war perception, which is that our own consciousness can never share the level of consciousness of dying soldiers and vice versa. In the course of war, after a certain time, we see war only as a familiar field with its signs and “special effects”.We no longer see people. What kind of people sat there in the trenches and were shot at by artillery—we don’t know. What they did for a living beforehand and whether they had families and children—we don’t know that either. Nor do we know what life the sudden war pulled them out of. And how they perceived it, how they experienced it and what they felt and how they dealt with thoughts about their possible death—we don’t know. We don’t know anything and we can’t imagine. How did these men accept the role of “cannon fodder”—this whole cruel ordeal? Human rationalism works like this: Unconsciously, we try to abstract from a traumatic reality. As a result, unfortunately, we ignore the catastrophe itself. Reality is absent. We hardly notice it because we simply cannot imagine the reality of war, death. It is a paradox. We generally dislike seeing violence as it exists in reality. The only worthy response to the challenge of terrorism would be to radically change the rationale of our thinking. However, the clearer it becomes to us what is actually happening, the more we refuse to be aware of it. Humanity is unconsciously writing the story of its own end. Destruction of the world is possible today as never before. That is why we need to wake up from our sleep. The search for our own comfort always leads to the worst.

Cargo 200. Experimental projections on surfaces. 5.7., 60 × 70 × 9 cm, variable dimensions (pine wood planks)

Acrylic, gesso and wooden board, pine wood planks, 2024. Close-up

Cargo 200. Experimental projections on surfaces. 5.7., 60 × 70 × 9 cm, variable dimensions (pine wood planks)

Acrylic, gesso and wooden board, pine wood planks, 2024. Close-up

Cargo 200. Experimental projections on surfaces

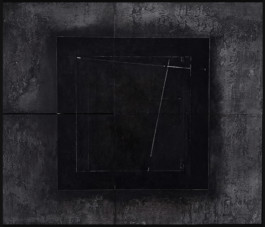

Installation view, Cargo 200. Experimental projections on surfaces. 5.7., 60 × 70 × 9 cm, variable dimensions (pine wood planks), Acrylic, gesso and wooden board, pine wood planks, Installation view at Kuenstlerhaus Sootbörn, Hamburg, DE, 2024

The long wooden elements in the installation Cargo 200. Experimental Projections on Surfaces. 5.7. are constructivist details, referencing the dream of a better world once envisioned by the constructivists. But what went wrong? We are now living in that imagined "future," and yet a better world remains out of reach. This work also employs the technique of iconography, though without specific religious figures. The black square represents a burial site. Since we do not know all the dead, their names, their stories, we can barely make out a few coffins in the overhead projection. The piece, taken as a whole, speaks to war as a broader phenomenon, not just a comment on current events. Through her visual and symbolic language, the artist addresses the cyclical recurrence of world-historical events. Themes of violence and resistance are deeply embedded in the human condition. Our capacity to adapt to the senselessness of war and tragedy, regardless of scale, stands in stark contrast to our awareness of their devastating consequences. Catastrophes leave indelible scars on the human soul.

Sofiia’s work does not offer comfort or resolution. Instead, it demands engagement—a challenge to viewers to recognize their role within the cycles of history and to reflect on the choices that either sustain or disrupt them. Violence does not return—it never leaves. Resistance is not heroism, but the final tremor of a being unwilling to yield to the void. The artist offers no salvation; she charts the anatomy of despair, showing that lucidity is not a virtue, but a burden too heavy for most to bear.

Cargo 200 is a term from military jargon. It refers to the transport of those killed in war back home. For the transport, the body of the deceased is placed in a special container, usually made of zinc. In my project, I use the method of “objectification” of my subjective war experiences by intuitively re-enacting the death of fellow citizens and soldiers through an experimental “an-ordering” on surfaces. This process captures the event rationally and insensitively, which is known to be a consequence of habituation to war. In war, the imaginary has no connection with reality. The traumatic nature of the reality of war is beyond our imagination. Overcome by this reality, we nevertheless cannot comprehend the fear of the possibility of our own death, which is unimaginable to us. When we think about our own death, we can be horrified, but when we talk about the death of thousands, the impossibility of mathematically multiplying the horror prevents us from trying to comprehend it. The world of war is made up of its own signs, most of which have hardly changed over the millennia. It is a series of archaic symbols that stand for center/periphery, order/chaos, vertical/horizontal, good/evil, life/death, victory/defeat, friend/foe. This series of works explores the problem of war perception, which is that our own consciousness can never share the level of consciousness of dying soldiers and vice versa. In the course of war, after a certain time, we see war only as a familiar field with its signs and “special effects”.We no longer see people. What kind of people sat there in the trenches and were shot at by artillery—we don’t know. What they did for a living beforehand and whether they had families and children—we don’t know that either. Nor do we know what life the sudden war pulled them out of. And how they perceived it, how they experienced it and what they felt and how they dealt with thoughts about their possible death—we don’t know. We don’t know anything and we can’t imagine. How did these men accept the role of “cannon fodder”—this whole cruel ordeal? Human rationalism works like this: Unconsciously, we try to abstract from a traumatic reality. As a result, unfortunately, we ignore the catastrophe itself. Reality is absent. We hardly notice it because we simply cannot imagine the reality of war, death. It is a paradox. We generally dislike seeing violence as it exists in reality. The only worthy response to the challenge of terrorism would be to radically change the rationale of our thinking. However, the clearer it becomes to us what is actually happening, the more we refuse to be aware of it. Humanity is unconsciously writing the story of its own end. Destruction of the world is possible today as never before. That is why we need to wake up from our sleep. The search for our own comfort always leads to the worst.

Cargo 200. Experimental projections on surfaces. 5.7., 60 × 70 × 9 cm, variable dimensions (pine wood planks)

Acrylic, gesso and wooden board, pine wood planks, 2024. Close-up